The voluntary Medicare Part D program was implemented on January 1, 2006, and of the 65 million Americans covered by Medicare in 2022, Part D provided prescription drug coverage for 49 million1 (or 75%). Part D costs are funded by its various participants—beneficiaries, the federal government, state governments (for beneficiaries also eligible for Medicaid), and pharmaceutical manufacturers. Beneficiaries can choose to enroll in either a stand-alone prescription drug plan (PDP) to supplement traditional Medicare or a Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug (MAPD) plan that includes Part D benefits.

Between 2007 and 2020, the total Part D spend by the federal government, through various programs (providing direct subsidies, federal reinsurance, and low-income subsidies) has increased. Federal government spend in 2007 was $46.2 billion compared to $91.7 billion in 2020—an increase of 5.4% per year.2 In addition, beneficiaries can experience high out-of-pocket costs, especially in the catastrophic benefit phase, due to their out-of-pocket costs not being capped.3 A study published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) found that more than 5 million Medicare beneficiaries struggled to afford prescription drugs in 2019.4

In an effort to curb federal government and patient spending, several drug pricing reforms were included in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which was signed into law on August 18, 2022.5 These reforms began taking effect in 2023 and include changes to the Part D benefit design as well as the introduction of a new drug price inflation control.

What is a prescription drug rebate?

Prescription drug rebates are an important aspect of the funds flow and financing of pharmaceutical benefits in the United States, including insurance programs. There are generally seven stakeholders in the chain of prescription drug benefits: pharmaceutical manufacturers, health insurers, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), pharmacies, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), wholesalers, group purchasing organizations (GPOs), and Medicare beneficiaries (see Figure 1 for an overview of each entity’s role and examples). Each of these stakeholders is affected by rebates.6 Of the seven stakeholders, four are financially responsible for funding Part D costs—pharmaceutical manufacturers, health insurers, CMS, and Medicare beneficiaries—whereas the others are intermediaries.

A rebate is a retrospective payment made by the seller to the buyer, typically as a buyer’s incentive. Prescription drug manufacturer rebates are generally paid by a pharmaceutical manufacturer to a PBM, which negotiates on behalf of, and shares rebates with the payer and, in the case of Medicare Part D, shares a portion with CMS. This type of rebate is mostly used for brand-name prescription drugs in competitive therapeutic classes where there are interchangeable products (rarely for generics) and aims to incentivize PBMs and health insurers to:

- Include the pharmaceutical manufacturer’s product(s) on the PBM’s formularies.

- Exclude competitor product(s) from the PBM’s formularies.

- Obtain preferred “tier” placement or remove step edits for the manufacturer’s product(s).

Note that current Part D policy requires Part D plans to include on their formularies all drugs from six protected classes7 (i.e., antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, immunosuppressants for treatment of transplant rejection, antiretrovirals, and antineoplastics), which generally have low or no rebates.

Figure 1: Key stakeholders in the Medicare Part D prescription drug distribution chain

| STAKEHOLDER | ROLE | EXAMPLE ORGANIZATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical manufacturer | Develop and market prescription medications. | Genentech, Pfizer, Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, AbbVie |

| Health insurer (Medicare Part D plan) | Provide insurance products to patients that cover healthcare services, including prescription drugs. | Aetna, Cigna, Humana, Elevance, Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS), CMS |

| Pharmacy | Dispense pharmaceutical drugs to patients. | Walgreens, Rite Aid, Duane Reade, CVS, mail order |

| Pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) | Intermediary between the health insurer, pharmaceutical manufacturer, and the pharmacy. Develop and maintain formularies for health insurers, negotiate rebates and discounts with manufacturers and pharmacies. | Caremark (part of CVS), Express Scripts (part of Cigna), Optum Rx (part of UnitedHealth) |

| Wholesaler/distributor | Distribute pharmaceutical drugs from the pharmaceutical manufacturer to the pharmacy. | AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, McKesson |

| Group purchasing organization (GPO) | Assist providers with purchasing by using volume to negotiate rebates, discounts, and other price concessions from vendors, including manufacturers. | Zinc (part of CVS), Ascent (part of Cigna), Vizient, Health Trust |

| Beneficiary/patient | Individuals with Medicare Part D coverage. | Beneficiary/patient |

Another type of prescription drug rebate is a “pharmacy rebate,” which is paid by pharmacies to PBMs and, for Part D, is passed through to the health insurer. Health insurers with preferred pharmacy networks may receive pharmacy rebates when beneficiaries go to certain pharmacies, which may be encouraged through lower copays. Pharmacy rebates for certain drugs may help steer utilization to certain pharmacies and drugs. Based on Milliman research, for some health insurers, pharmacy rebates can be as much as 30% of total rebates. CMS has finalized a rule (CMS-4192-F8) that requires Part D plans to apply all network pharmacy rebates to the point-of-sale (POS) price starting January 1, 2024. POS rebates are passed to the patient when the prescription is filled and, therefore, can result in reduced cost sharing to the patient if they are paying a coinsurance (a percentage of the drug’s cost).

A formulary is the list of prescription drugs that a health insurer will cover. Typically, a formulary is divided into multiple tiers (five or six in Part D formularies). Each tier is associated with different levels of patient cost sharing, and different products are assigned to different tiers based on a variety of factors. Formularies are usually developed by PBMs on behalf of their clients, health insurers, and the PBM also negotiates prescription drug prices and rebates with pharmaceutical manufacturers. Formulary tiers may be designed to promote lower-cost prescription drugs; for example, a lower-cost generic prescription drug may require a $5 copay, a preferred brand-name prescription drug with a rebate may require a $45 copay, and a non-preferred brand-name prescription drug without a rebate may require a $100 copay or 40% coinsurance. Therefore, rebates can incentivize health insurers to put brand-name drugs on a preferred brand-name tier, which through lower patient cost sharing may translate to patients filling more scripts. Formulary placement may be designed to improve adherence and encourage appropriate medication use, as well as optimize the PBM’s or health insurer’s revenue.

Rebate and other administrative fees are typically trade secrets and vary widely by brand, therapeutic class, pharmaceutical manufacturer, PBM, and health insurer, and are often highest for brands in non-protected therapeutic classes with competing products.

This secrecy makes meaningful cost comparisons of competing brands using public “list price” metrics difficult. Rebates therefore create a black box in the prescription drug financing chain—often the health insurer does not know how much the pharmaceutical manufacturers’ rebates are for a given drug. At best, health insurers know what the negotiated rebates are, and how much of it is retained by the PBMs before passing the remainder to the health insurer. While average rebates are close to 30% of the drug’s cost, some brands have no rebates and others are believed to offer rebates of over 70%.

What is the impact of rebates?

Together with contracted prices, rebates are a key factor in health insurers’ choices about whether to include a specific prescription drug on a Part D formulary and in which tier. Therefore, rebates impact the finances of all stakeholders in the prescription drug distribution chain, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Rebates in the Medicare Part D prescription drug distribution chain9

Patients: Prescription drug manufacturer rebates are a key determinant of whether a particular drug is covered by a patient’s plan and, if covered, the patient’s out-of-pocket (OOP) cost. Patients usually pay a coinsurance or a higher copay for higher-cost brands and a coinsurance percentage for specialty drugs; because the coinsurance percentage is typically applied to the price of the prescription drug before subtracting the manufacturer rebate, patients often pay a higher percentage of the insurer’s drug cost net of rebates than the listed coinsurance percentage. However, due to the new CMS rule discussed above (CMS-4192-F), this will no longer be the case for pharmacy rebates.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers: Pharmaceutical manufacturers pay rebates to have their products on formularies, and therefore maintain or increase sales for their products. However, they also contribute to the growing spread between pharmaceutical manufacturers’ pre-rebate “gross” and post-rebate “net” revenue. In recent years, pharmaceutical manufacturers have reported actual revenue of 40% to 75%10 of gross sales due to rebates and discounts.

Health insurers: Rebates can help health insurers reduce premiums and provide more robust benefits (such as lower cost sharing). Health insurers will continue to rely on rebates as they have a greater impact on setting premiums and benefits than price discounts.

CMS: Because Part D rebates are shared with CMS, the federal government’s liability for the Part D program is also affected by rebates. The more scripts filled in the catastrophic benefit phase (where the health insurer shares rebates with CMS), the more rebate revenue CMS receives. Federal subsidies are also affected by rebates.

PBMs: Rebates are an important component of PBMs’ business models as they negotiate rebates with pharmaceutical manufacturers on behalf of health insurers. For Part D plans, rebates are typically fully passed through to the health insurer and the PBM generates revenue through other fees (example—per script fees).

Wholesalers: Rebates play an important role in formulary decisions and can therefore influence the demand for specific prescription drug brands from these wholesalers.

Pharmacies: Pharmacy rebates are typically associated with preferred pharmacy networks and are impacted by the CMS rule discussed above (CMS-4192-F). In addition, as with wholesalers, the demand of specific prescription drug brands that a pharmacy dispenses is influenced by rebates.

GPOs: Rebates are one of the price concessions GPOs may negotiate on behalf of their clients (often healthcare providers). That can translate into which products are stocked and utilized by healthcare providers.

How will the IRA impact rebates?

In a pre-IRA world (see Figure 3), the standard Part D benefit design includes the following phases:11

- Deductible: Beneficiaries pay 100% of costs.

- Initial coverage limit (ICL): Beneficiaries pay 25% of costs, plans pay 75% up to an ICL.

- Coverage gap or “donut hole”: Non-low-income beneficiaries pay 25% of drug costs, manufacturers pay 70% of ingredient costs for applicable drugs,12 and plan sponsors pay 5% and 75% for applicable and non-applicable drugs, respectively. For low-income beneficiaries, the member and the low-income cost-sharing (LICS) subsidy cover 100% of drug costs.

- Catastrophic: The federal government pays 80% of drug costs through reinsurance, the member pays 5%, and the plan pays 15%. Beneficiaries enter this phase when their true out-of-pocket (TrOOP) costs for the year cross a predetermined limit (this limit is $7,400 for 2023).

Benefit redesign

Starting in 2025, the IRA’s changes to the Medicare Part D benefit design will be implemented (see Figure 3), including:13

- The introduction of a member out-of-pocket (MOOP) amount that caps total patient cost sharing at $2,000 per year

- The elimination of the coverage gap phase

- The health insurer liability will increase to 60% in the catastrophic phase

- The shift of manufacturer liability for applicable drugs from the coverage gap phase only (currently 70%) to the initial coverage phase (10%) and the catastrophic phase (20%)

The IRA changes to the Medicare Part D benefit design will likely have an impact on current dynamics between PBMs, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and health insurers as the additional liability that health insurers will take on in the post-threshold phase will increase the importance of controlling spending by higher-cost patients.15 Under the IRA, higher-priced/higher-rebated products may be less profitable to health insurers than the lower-priced/lower-rebated competitors. Health insurers could increase their use of utilization management tools, such as prior authorizations and step edits, to manage costs. Tactics are likely to vary widely by health insurer, therapeutic class, and pharmaceutical manufacturer. For some drug classes, pharmaceutical manufacturers may choose to keep rebates the same and health insurers may not see their liabilities change for impacted patients. In other scenarios, health insurers may put additional pressure on pharmaceutical manufacturers to offer more rebates in order to offset increased liability for particular patient populations.

While there are many changes to the Medicare Part D benefit design post-IRA, at a high level the various changes can be thought of as roughly zero-sum for the government and insurers. For example, while health insurer liability increases dramatically, the government will pay for that increase (through increased direct subsidy payments). The greatly reduced government liability in the catastrophic phase should be offset by the increase in government payments to health insurers in aggregate. However, at a more detailed level, the dynamics and incentives will change dramatically, and the distribution of benefits will vary by stakeholder. We illustrate some of these details for rebates below.

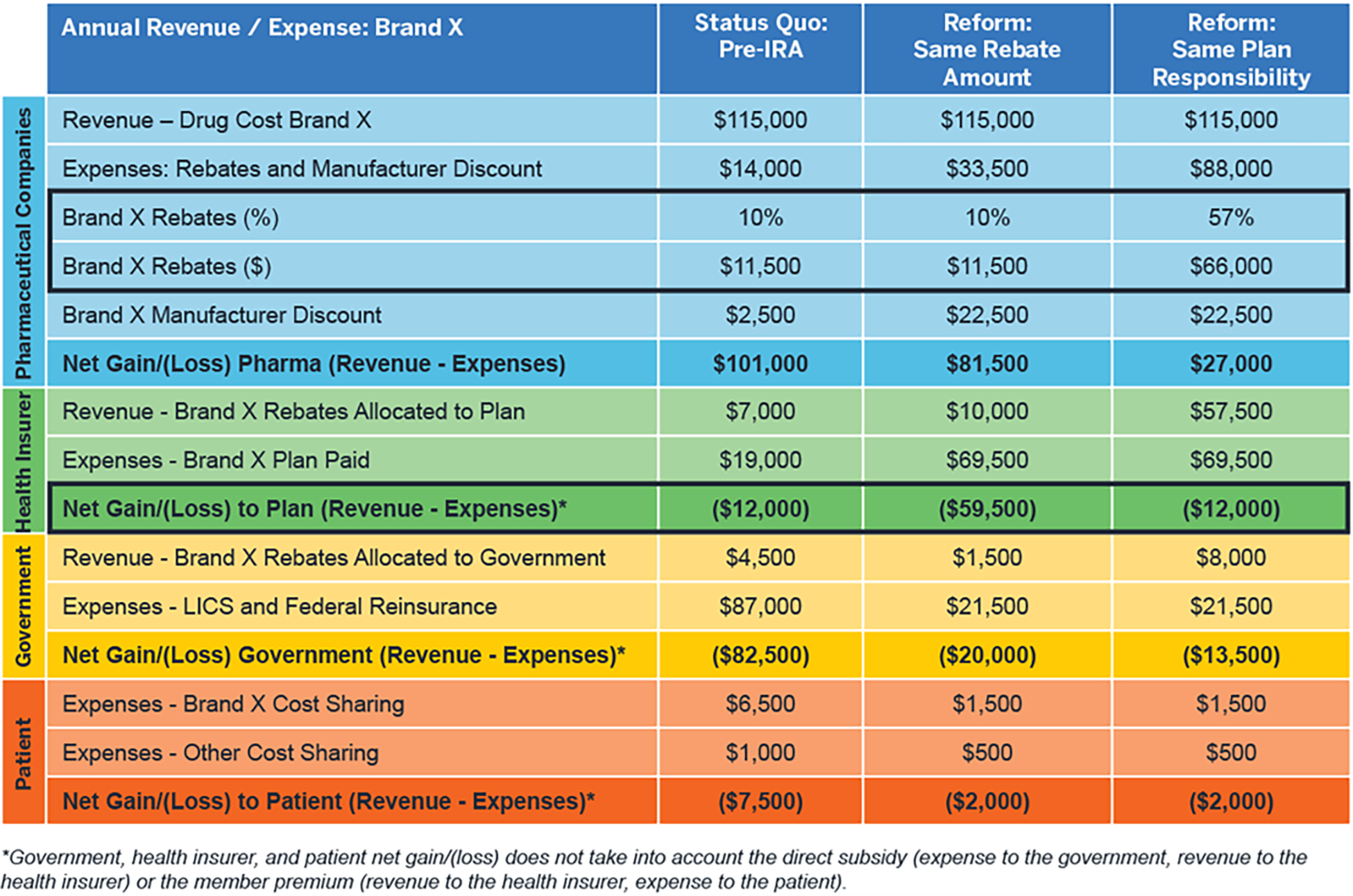

Figure 4 shows average costs by stakeholder for a patient using a Part D specialty drug (“Brand X”) with a 10% rebate by stakeholder in the pre-IRA market. It then shows the impact of two options for post-IRA rebates: keeping the rebates the same versus increasing them so that the cost to the health insurer (which ultimately is funded by the patient and the government) is the same as it would be in the pre-IRA market. This illustration shows that, for health insurer costs to remain constant, the manufacturer rebates would have to increase from 10% to approximately 60% of the drug cost.

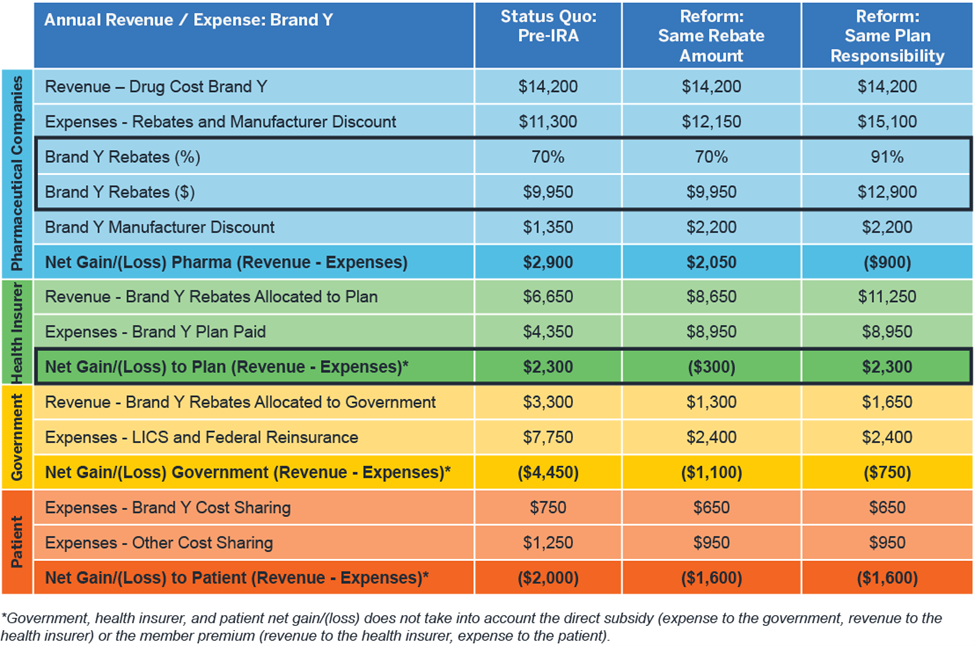

Figure 5 demonstrates the impact on rebates post-IRA for a Part D brand-name drug (“Brand Y”) that currently has higher manufacturer rebates. Under the IRA, the manufacturer would have to pay rebates over 90% to keep the health insurer’s profitability for this patient population the same as in the pre-IRA status quo because the health insurer will continue to share rebates with the government but will retain a higher proportion of the rebates under the IRA. Therefore, some health insurers may look to renegotiate their contracts to account for the additional costs they will take on in the post-IRA market. These renegotiations could also contemplate components of the contract other than rebates—such as drug price discounts and administrative fees. On the other hand, as health insurer costs increase, bid amounts16 and CMS direct subsidy amounts should also increase. On a population level, the health insurer’s losses could be offset by increases in the CMS direct subsidy payments.

Figure 4: Impact of IRA benefit redesign on Part D stakeholder financials – Brand X, low rebates

Figure 5: Impact of IRA benefit redesign on Part D stakeholder financials – Brand Y, high rebates

Federal price negotiation

Starting in 2026, HHS will begin negotiating maximum fair prices for single source drugs and biologics in Medicare Part D. On August 29, 2023, the 10 selected Part D drugs for price negotiation in 2026 were announced by CMS, as shown in Figure 6.17

Figure 6: 10 selected Part D drugs for price negotiation in 2026

| Drug | Manufacturer | Drug | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eliquis | Bristol Myers Squibb | Entresto | Novartis |

| Jardiance | Boehringer Ingelheim | Enbrel | Amgen |

| Xarelto | Janssen | Imbruvica | Pharmacyclics/AbbVie |

| Januvia | Merck | Stelara | Janssen |

| Farxiga | AstraZeneca | Novolog | Novo Nordisk |

Drugs selected for price negotiation will be required to be on formularies, but tier placement is not specified. Manufacturers of selected drugs may or may not adjust their rebates as a result of price negotiation, which could have a downstream impact on the rebate strategy of a selected product’s competitors. Because health insurers will have higher liability post-IRA, health insurers may try to push patients toward generic drugs and continue to pursue rebates on brand-name and specialty products.

Inflation rebate

The IRA also includes the introduction of a new type of rebate, the “inflation rebate,” which aims to shift some of the cost of rising drug prices to the pharmaceutical manufacturer rather than patients and CMS. If a change in drug cost is higher than the change in the consumer price index for urban consumers (CPI-U), then the drug manufacturer will pay the difference to CMS. Figure 7 displays the Q2 2023 (in blue) and Q3 2023 (in green) Part B drugs that will be impacted by the IRA inflation rebate.18, 19

Figure 7: Q2 and Q3 2023 Part B drugs impacted by IRA inflation rebate

The inflation rebate may encourage manufacturers to launch new drugs at higher prices, because the inflation rebate will penalize them for increasing the price in the future. Due to potentially higher launch prices, plans may try to negotiate higher rebates to keep their net cost down.

Conclusion

The IRA will impact the Medicare Part D industry for all stakeholders, including the role of prescription drug rebates on health insurers’ financials. For some stakeholders, the financial incentives will change, as will decisions about formularies, rebates, and prices. With the IRA’s Part D benefit redesign, the tactics health insurers use to manage costs will likely change, and patients may face fewer financial obstacles but more administrative obstacles in order to access higher-priced therapies.

1 Kaiser Family Foundation (October 19, 2022). An Overview of the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/an-overview-of-the-medicare-part-d-prescription-drug-benefit/.

2 MedPAC (March 2022). Chapter 13: The Medicare Prescription Drug Program (Part D): Status Report. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Mar22_MedPAC_ReportToCongress_Ch13_SEC.pdf.

3 Kaiser Family Foundation (January 29, 2019). 10 Essential Facts About Medicare and Prescription Drug Spending. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.kff.org/infographic/10-essential-facts-about-medicare-and-prescription-drug-spending/. #9.

4 HHS (January 19, 2019). Prescription Drug Affordability Among Medicare Beneficiaries. ASPE Data Point. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1e2879846aa54939c56efeec9c6f96f0/prescription-drug-affordability.pdf.

5 The full text of the IRA is available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text.

6 For more background, see https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/a-primer-on-prescription-drug-rebates-insights-into-why-rebates-are-a-target-for-reducing.

7 CMS (May 16, 2019). Medicare Advantage and Part D Drug Pricing Final Rule (CMS-4180-F). Fact Sheet. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-advantage-and-part-d-drug-pricing-final-rule-cms-4180-f.

8 CMS (April 29, 2022). CY 2023 Medicare Advantage and Part D Final Rule (CMS-4192-F). Fact Sheet. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cy-2023-medicare-advantage-and-part-d-final-rule-cms-4192-f.

9 Acronyms used in Figure 2: CGDP: Medicare Coverage Gap Discount Program. MDP: Manufacturer Discount Program. LICS, LIPS: low-income cost sharing and low-income premium subsidies.

10 Fein, A.J. (June 13, 2023). Gross-to-Net Bubble Update: 2022 Pricing Realities at 10 Top Drugmakers. Drug Channels. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.drugchannels.net/2023/06/gross-to-net-bubble-update-2022-pricing.html.

11 Klaisner, J.K., Pierce, K., & Cires, A. (November 30, 2021). The Build Back Better (BBB) Act: Detailed Summary of Medicare Parts B and D Changes. Milliman Insight. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/the-build-back-better-act-medicare-parts-b-and-d-key-changes.

12 Manufacturer’s discount in the catastrophic phase counts toward beneficiaries’ TrOOP accumulations.

13 Cline, M., Karcher, J., Klaisner, J.K., & Klein, M. (August 18, 2022). Weathering the Reform Storm: The Inflation Reduction Act’s Changes to Medicare and Other Healthcare Markets. Milliman Insight. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/weathering-the-reform-storm.

14 Applicable drugs are Part D prescription drugs approved under new drug applications (NDAs) or licensed under biologics license applications (BLAs). They are generally brand-name Part D drugs, including insulin and Part D vaccines

15 Gergen, R., Leciejewski, Z., Koenig, D., & Pierce, K. (January 2023). Medicare Part D Risk and Claim Cost Changes With the Inflation Reduction Act. Milliman White Paper. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.milliman.com/-/media/milliman/pdfs/2023-articles/1-18-23_part-d-risk-ira-article.ashx.

16 Bid amount is the plan’s costs for standard Part D benefits plus administrative cost plus margin.

17 Cates, J., Holcomb, K.M., Klaisner, J.K., & Swenson, R.L. (September 12, 2023). Medicare Price Negotiation: A Paradigm Shift in Part D Access and Cost. Milliman White Paper. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/medicare-price-negotiation-paradigm-shift-part-d-access-cost.

18 CMS (September 2023). Reduced Coinsurance for Certain Part B Rebatable Drugs Under the Medicare Prescription Drug Inflation Rebate Program. Applicable April 1-June 30, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.cms.gov/files/document/reduced-coinsurance-part-b-rebatable-drugs-apr-1-june-30.pdf.

19 CMS (September 2023). Reduced Coinsurance for Certain Part B Rebatable Drugs Under the Medicare Prescription Drug Inflation Rebate Program. Applicable July 1-September 30, 2023. Retrieved September 22, 2023, from https://www.cms.gov/files/document/reduced-coinsurance-part-b-rebatable-drugs-6823.pdf.