Introduction: The continued impact of redlining

While U.S. housing regulations have changed significantly over the past 90 years, at least one historical policy has a pronounced and ongoing impact on many aspects of affected individuals’ daily lives today: redlining.

In the 1930s, the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) used redlining to quantify mortgage riskiness in 239 American cities. The process collected information about a location’s housing stock and recent sale and rent prices. It also noted “the racial and ethnic identity and class of residents” and used this data to assign the neighborhood a “grade,” or level of risk, for real estate investment.2 In the HOLC’s estimation, neighborhoods with the lowest grade—depicted in red on maps—were flagged as “hazardous,” and “conservative, responsible lenders” would avoid issuing mortgages there.3

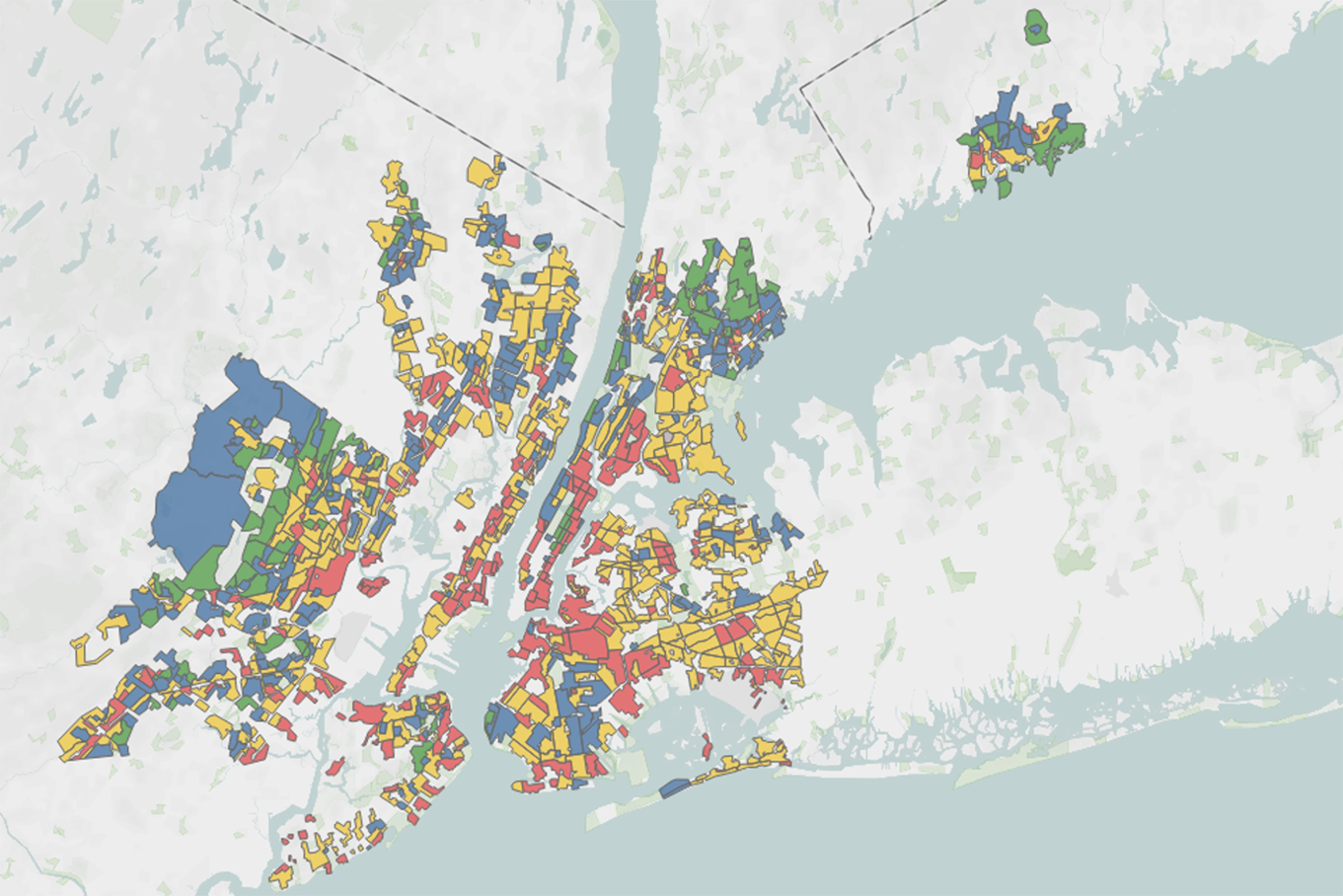

As an example, Figure 1 shows how redlining was applied to portions of New Jersey and New York state: green areas were determined by HOLC to be the “best” areas to lend money and posed a minimal risk for banks and mortgage lenders; blue areas were determined by HOLC to be “still desirable,” but posed slightly more risk than green areas; yellow areas were determined by HOLC to be “definitely declining”; and red areas were determined by HOLC to be “hazardous” and were to be avoided; hence the term redlining.4

Figure 1: Example of HOLC categories applied to neighborhoods in New Jersey and New York state

Source: Mapping Inequality. Data retrieved January 26, 2022. Hand-drawn color-coded maps visualized HOLC staff members’ assigned grades to residential neighborhoods to reflect their “mortgage security” in the 1930s.The Mapping Inequality project offers spatial data, detailing neighborhoods and their HOLC-grades.5

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 put an end to such discriminatory housing and lending practices. However, even today, formerly redlined neighborhoods still experience a lack of investment of both public and private resources. In fact, scholars have characterized redlining practices “as some of the most important factors in preserving racial segregation, intergenerational poverty, and the continued wealth gap between white Americans and most other groups in the U.S.”6

Given that other studies have already demonstrated the prolonged impact of redlining on access to public services, generational wealth, and some health outcomes, our study seeks to better understand and quantify the potential association between this historical discriminatory practice and current U.S. health outcomes.

Key findings

We identified Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries living in ZIP Codes that corresponded to HOLC historically redlined neighborhoods. Compared with the beneficiaries living in nonhistorically redlined areas, more of the beneficiaries in historically redlined areas were younger than age 65, as shown in Figure 2. While most Medicare beneficiaries are at least 65 years old7—the usual age of eligibility—Medicare also is available to younger beneficiaries who are disabled and/or have certain diagnoses, including patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which often requires dialysis. Because most beneficiaries under age 65 require a disability and/or diagnosis to qualify, beneficiaries in historically redlined areas are likely to be less healthy than beneficiaries in nonhistorically redlined areas.

Figure 2: Medicare FFS beneficiaries by HOLC location grouping and age categories, 2019

Indeed, we observed that beneficiaries residing in historically redlined areas had notably higher healthcare utilization compared to those living in the green areas for nearly all service categories that we examined, as shown in Figure 3. In particular, compared with FFS beneficiaries living in green areas, residents of historically redlined areas had:

- 52% more dialysis use

- 37% more inpatient treatment for substance use disorders

- 31% more use of intensive outpatient psychiatric care

The use of dialysis points to a higher prevalence and burden of kidney disease in historically redlined areas, while substance use disorders and psychiatric care8most likely correlate with the built environment and stress burden as a result of lingering financial and other inequities in historically redlined areas.9 Research to confirm these linkages is ongoing.

Figure 3: Healthcare metrics for Medicare FFS beneficiaries by HOLC location grouping, 2019

| Measure | HOLC Grades | Redlined Areas as Percent of Green Areas |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historically Redlined Areas |

Yellow Areas |

Blue Areas |

Green Areas |

||

| Membership Split* | 24% | 43% | 24% | 9% | 265% |

| Average Age (years) | 70 | 70 | 71 | 72 | |

| Percentage Under Age 65 Years* | 20% | 19% | 16% | 11% | 178% |

| Percentage Dual-Eligible, End-Stage Renal Disease, Hospice* | 34% | 30% | 23% | 15% | 221% |

| Risk Score | 1.22 | 1.20 | 1.15 | 1.10 | 111% |

| Allowed Medical and Prescription Drug Costs PMPM** | $1,597 | $1,532 | $1,415 | $1,275 | 125% |

| Inpatient Admits per 1,000 Members | 417 | 405 | 366 | 331 | 126% |

| Inpatient Substance Use Disorders per 1,000 Members | 4.6 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 199% |

| Outpatient Visits per 1,000 Members | 9,240 | 8,403 | 7,803 | 6,957 | 133% |

| Emergency Department Visits per 1,000 Members | 469 | 413 | 377 | 332 | 141% |

| Outpatient Psychiatric – Intensive per 1,000 Members | 50 | 39 | 37 | 25 | 195% |

| Dialysis per 1,000 Members | 1,371 | 1,161 | 936 | 621 | 221% |

| Professional Services per 1,000 Members | 28,811 | 29,371 | 28,927 | 29,497 | 98% |

| Preventive Services per 1,000 Members Outpatient (defined by facility claims)*** Professional (defined by physician claims)† |

635 2,402 |

585 2,507 |

567 2,658 |

527 2,863 |

120% 84% |

* Demographic splits based on Medicare Part A member months.

** Costs are inclusive of Medicare only; no Medicaid costs for dual-eligibles are included.

*** Outpatient preventive services performed in a hospital outpatient department or freestanding facility as required under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) include colonoscopy, mammography, lab, and other preventive services. Many of these services must meet additional requirements such as gender, age, or diagnosis.

† Professional preventive services include immunizations, physical exams, and other preventive services such as colonoscopy, mammography, lab, and other services required under the ACA. Many of these services must meet additional requirements such as gender, age, or diagnosis

Among beneficiaries in historically redlined areas, the use of professional services—which include preventive care—was equal to or lower than the usage of these services in historically non-redlined areas. We also found that residents of historically redlined areas had an average risk score of 1.22 and an average per-member-per-month (PMPM) spend of $1,597, while residents in green areas had an average risk score of 1.10 and an average PMPM spend of $1,275.

The differentials in healthcare costs and utilization per Figure 3 are often larger than what would be explained by risk score differentials, which indicates that adjusters based on risk scores will not always resolve underlying disparities. Thus, given the possibility for confounding issues in healthcare outcomes (e.g., population composition, service mix, access), we also include a comparison of the median Social Deprivation Index (SDI) scores by HOLC location category.

SDI is “a composite measure of area level deprivation based on seven demographic characteristics collected in the American Community Survey and used to quantify the socioeconomic variation in health outcomes.”10 Specifically, SDI measures the percentages of:

- People living in poverty

- People with less than 12 years of education

- Single-parent households

- People living in rented housing units

- People living in an overcrowded housing unit

- Households without a car

- Adults under age 65 years who are unemployed

Figure 4 demonstrates how pronounced the differences in SDI score can be by HOLC location grouping.

Figure 4: Median Social Deprivation Index score by HOLC location category

Methodology and assumptions

We began by looking at data for Medicare FFS beneficiaries and sought to determine the historical HOLC “grade” of their locations. To do this, we accessed resources available through Mapping Inequality, the government-sponsored research project led by researchers at the University of Richmond that provides digital versions of HOLC’s original hand-drawn maps.11 From there, we could map HOLC categories to ZIP Code Tabulation Areas for the cities where redlining practices were used.12

Next, we mapped Medicare FFS beneficiaries to HOLC categories using the five-digit ZIP Code for their residences, via the uniform coding system, in the 100% research identifiable files (RIFs) for calendar year 2019. As ZIP Codes often contain more than one HOLC category, a member’s claim data and enrollment were split based on the population over age 65 years in a ZIP Code assigned to each HOLC category. For example, the enrollment and claims data for a member residing in ZIP Code 11235 of Brooklyn, New York, was split according to the percentages shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Example enrollment and claims data split for member residing in ZIP Code 11235

| ZIP Code | Historically Redlined Areas |

Yellow Area | Blue Area | Green Area | None |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11235 | 30% | 55% | 4% | 0% | 11% |

Finally, we used standardized counting rules from Milliman’s Health Cost Guideline™ Grouper software to organize a summary of medical claims, from which we then analyzed differences in average risk score (a statistical measure of health status and resource use), allowed costs (healthcare spend), and utilization across a number of service categories by HOLC location grouping. Outpatient and professional service utilization counting varied based on the service and included visits, procedures, and units. Our utilization and cost results were not normalized for differences in population demographics although risk scores are influenced by demographic differences.

We also determined the current median SDI score—described in more detail above—for each HOLC location grouping. The SDI is maintained by the Robert Graham Center to help assess the impact of various social determinants of health on health outcomes and to help direct resources toward programs more likely to be effective.13

We were able to map approximately 2.8 million beneficiaries, or about 7.4% of the total Medicare FFS population nationwide, to an area graded by the HOLC. Almost 11% of the total Medicare FFS population had ZIP Codes not considered in the HOLC exercise. The percentages shown are based on Part A, which provides coverage for inpatient services.

Conclusions

Redlining’s lingering effects, including its impact on the ongoing racial wealth gap, have been well documented.14 Our study adds to this understanding and can be helpful in the context of addressing health inequities. In particular, we find that utilization of certain services (e.g., dialysis, inpatient treatment for substance use disorders, and intensive outpatient psychiatric care) is significantly more pronounced in historically redlined areas than nonhistorically redlined areas.

While there is certainly a notable difference in other metrics studied (11% difference in risk scores and 25% difference in allowed costs), these differences may not accurately depict the full volume of the disparities tied to historically redlined areas. Risk scores depend on the extent to which beneficiaries seek care, their access to primary care, and accurate and thorough coding of an individual’s diagnoses recorded by a clinician during a health service, so risk scores may not fully capture differences in health status between areas with different levels of access to healthcare services and resources. Moreover, if clinicians in historically redlined areas are experiencing an overburdened caseload, their coding may not be as thorough as the coding in green areas, further depressing the risk score in historically redlined areas. Cost comparisons across HOLC location groupings can also be impacted by access issues as well as the mix of services available to beneficiaries. To the extent these geographies also are subject to different Medicare fee schedules, outlier payments, etc., the allowed cost relationships can be further distorted.

We also found that declining neighborhood “quality,” according to HOLC measures, corresponded to higher median SDI scores, following a consistent pattern from historically redlined to green areas. While redlining cannot be undone, ongoing research, including the findings from this study, can continue to draw attention to the myriad impacts of this historical policy and guide interventions to counteract, and ultimately end, its aftermath.

Considerations and limitations

First, our analysis was not designed to determine the statistical significance of the differences in healthcare costs observed or estimated, nor to prove the causation of these amounts.

Moreover, we did not quantify the severity of the conditions resulting in the differences in utilization by area. As noted above, the differences in risk score and allowed cost PMPM could be influenced by the mix of services as well as potential access issues; however, all neighborhoods assigned a HOLC grade were metropolitan (city) areas, and thus Medicare fee schedules and access to service by site of care are expected to be very similar.

Additionally, HOLC grades were only applied so certain metropolitan (city) areas in the United States and thus these findings are not necessarily generalizable to other areas of the United States, even to areas with similar racially based lending practices (e.g., housing covenants).

Finally, we did not normalize the results of each HOLC area for demographic mix (e.g., aged vs. disabled mix), mix of services, disease severity, SDI, etc. Please note that the decision not to normalize for these factors was intentional as the sources referenced throughout this paper draw the correlation between historically redlined areas and limited infrastructure investment, which exacerbates many of the healthcare outcomes noted above such that normalizing for the above mix differences and other factors would mask important differences in healthcare outcomes.

This Milliman report has been prepared for the specific purpose of observing differences in utilization of healthcare services by HOLC geographic classification grouping. This information should not be used for any other purpose.

The results presented herein are estimates based on carefully constructed actuarial models. Differences between our estimates and actual amounts depend on the extent to which actual experience conforms to the assumptions made for this analysis. It is certain that actual experience will not conform exactly to the assumptions used in this analysis.

In performing this analysis, we relied on the 100% Research Identifiable Files of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) along with HOLC geographic classifications. We have not audited or verified this data and other information but reviewed it for general reasonableness. If the underlying data or information is inaccurate or incomplete, the results of our analysis may likewise be inaccurate or incomplete.

In the version of Mapping Inequality used in this analysis, the spatial data was limited to residential areas that had been graded by the HOLC. Mapping Inequality has since added over 100 redlining maps typically representing communities with populations lower than 40,000 people. We did not update our analysis to incorporate these additions.

1 Based on a poster presented at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) conference in Boston, Massachusetts, May 7-10, 2023.

2 Nelson, Robert K., LaDale Winling, et al. "Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America." Edited by Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers. American Panorama: An Atlas of United States History, 2023. Accessed August 20, 2024 from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining.

5 Gerken Mathew, Batko Samantha , et al "Assessing the Legacies of Historical Redlining " Accessed August 21, 2024 from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/Addressing%20the%20Legacies%20of%20Historical%20Redlining.pdf.

6 Data and Performance Analytics Division, Racine County (September 29, 2020). Redlining and Racine County. Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/d13b4bab17cc46ed80aee3addfb805b2.

7 https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/f81aafbba0b331c71c6e8bc66512e25d/medicare-beneficiary-enrollment-ib.pdf. p5.

8 Mapping Inequality, op cit., Meier, H.C.S., Redlining and Health. Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/health.

9 Mapping Inequality, op cit., Hoffman, J.S., Hotter, Wetter, Sneezier, and Wheezier. Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/environment.

10 Robert Graham Center. Social Deprivation Index (SDI). Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://www.graham-center.org/maps-data-tools/social-deprivation-index.html.

11 Mapping Inequality, op cit. accessed January 26, 2022

12 U.S. Census Bureau. ZIP Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTAs). Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/zctas.html.

13 Robert Graham Center, Social Deprivation Index (SDI), op cit.

14 Townsley, J. & Miguel Andres, U. (June 24, 2021). SAVI. The Lasting Impacts of Segregation and Redlining. Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://www.savi.org/lasting-impacts-of-segregation/.